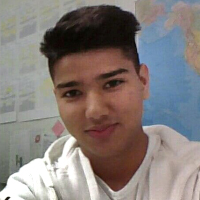

Alireza Norouzi

Alireza, the Eternal Migrant

Alireza Norouzi. Eighteen years of age. Born in the first days of spring. A son of Afghanistan. Born in a time where the dark and heavy shadow of the Taliban still reigned over people, when war was a fresh wound that could reopen any moment.

When his family fled destruction and death and migrated to Iran, Alireza was too young to have any memory of the dark past of his motherland. Their hope of a common language and culture with Iran died in the early days after migration. His childhood was spent under the heavy and humiliating glances of those who didn’t consider him and the likes of him to be anything but a third-class citizen. He had no identity card, no identity. He was an alien, a stranger. He could understand the language of the host country, which was the same as his mother tongue. But he couldn’t understand all that unkindness, all that discrimination. Can you imagine a bigger pain than fleeing war to a land in which people speak your mother tongue, but use that very language every day to deny you? For little Alireza, migration to Iran brought poverty, deprivation, and suffering. And what did he gain? Nothing, nada. Alas, to be content with that “nothing” was the only way for many Afghan migrants in Iran to continue their lives.

There were a small number of migrants who went through emigration. It wasn’t so easy to fly out of the big cage. The parents knew that you can only fly as long as they haven’t clipped your wings — although this time, there was talk of flying far, far away. To a land with a colder sun and shorter days.

He was a teenager when he went to Sweden along with his brother. Sweden’s climate differed from that of his motherland, but it had a warm and accepting embrace. For Alireza, this was an inchoate but hopeful beginning. This soon became his homeland, a place in which human dignity wasn’t missing, a place that gave him opportunity and a dare to dream.

For all the years that he lived with his brother in Sweden, his small and safe room was a center from which calm Greek ballads emanated. Alireza was happy with the minimum, but the ceiling of his wishes kept going up: He wanted to travel to space. He loved to discover. He wanted to be a pilot. As parents say, he wanted to be someone. He was the youngest child of a family who had spent all it ever had on the kids’ education. In his heart, he dreamed of a future that had been robbed of him, first by the Taliban and then by the Islamic Republic of Iran. But now the dreams didn’t feel so unachievable.

He had a brilliant mind for math and physics. But he picked computer sciences. To his sister, Latifa, he would speak of the innovations of the well-known entrepreneur Steve Jobs. The world of computers attracted him, and he studied computer engineering at university.

In addition to his little concerns and his big wishes, Alireza also had an impossible hope: To bring back the mother he had lost. He was 13 when he lost his mother. Thus began an endless suffering that led to his no-return trip to Iran. Losing his mother in his teenage years had deeply affected his personality. He was happy with his little student room. With the small and safe life he had built himself and the little he had of life. But he had repeatedly complained to his siblings of the death of their mother. He awaited a miracle. He wanted to find the patience that seemed impossible. He had heard that as the dust grows cold, the survivors become patient. He would dream of his mother, in her eternal sleep in a corner of Iran’s cold dust. And the temptation of returning to a country that reminded him of the bitter memories of childhood, discrimination, humiliation, and swearing. But sometimes the temptation of touching that little cold stone and the flowers he could put across the name of his mother overcame the bitterness of the past.

When the university winter holidays came, he decided to go back. But only for two weeks.

The last night of the journey, that damned night of January 8, he messaged his sister Latifa from the airport to say he had lost his travel documents. He had begged for the airport cameras to be activated, so he could find his documents and make it to the flight. When his eyes were shining because he found the passport and the boarding pass, when he went up the stairs of the plane, when he fastened his seatbelt, when he got his Greek album ready for the flight, when the plane took off, and he shed a tear or two for his mother, when he thought of coming back in a few years to touch the stone again, when the plane began to shake… in none of those moments, did he think this possible: Those who had considered him to be nothing for years were now trying to murder him. He couldn’t imagine that in a few hours, the most impossible dream would be the dream of his sister Latifa: “Dear Brother! God damn the airport’s cameras. I wish they had broken down and never helped you find your documents. I wish you were here, so we could celebrate your 19th birthday in a few days.”

In less than 24 hours, a man was sitting in the midst of the flight debris, crying, “He was 18 years old. He was my brother. He had come from Sweden and wanted to go back to Sweden. We are Afghans. Alireza Norouzi. He had been in Iran for 15 days. I found out on the phone. I read the news of the crash. His family are abroad.”

The man cried and thought to himself: How could this bloody debris, these destroyed bodies, be so similar to the shredded bodies he had seen in the days of the Taliban’s dominance? He thought of the day he had left Afghanistan with his brother. He thought of their years of life in Iran without identity and hope for the future. Without speaking a word, he had concluded: The Islamic Republic did to the young Alireza what the Taliban wanted to do for years but couldn’t. It denied him first — and killed him at last.